1) Brief Summary of the Case

The famous Svensson case concerned literary works (news articles) which have been initially published by the Swedish publisher “Göteborgs-Posten”, both in its newspaper and its official website. The claimants had not applied any specific technical measures for restricting the access to its protected content (e.g. no pay walls or registration forms), which was freely available to internet users. On the other hand, the defendant was a Swedish startup company named “Retriever Sverige AB” that offered to its users a news aggregation service. The service allowed the users to access articles that were indexed and categorized, by means of a clickable frame which was placed on the graphic interface of the website and upon its activation could redirect them to the selected article. The applicants filed a lawsuit asking for compensation, considering that their right of communication to the public was violated by the inclusion of clickable Internet links which were redirecting users to their articles. In this respect, the Swedish Court filed a request for a preliminary ruling asking from the CJEU to assess whether the provision of clickable links under the aforementioned circumstances was a violation of the applican’s right of communication to the public.

2) The Court’s ruling

As a first step, the CJEU held that the provision of clickable links to protected material that was published without any access restrictions on another website, amounts to an “act of making available” and therefore “an act of communication” within the meaning of Art. 3(1) of the InfoSoc Directive, since it provides the users of the first website with direct access to those works. The Court reached this interim conclusion based on the settled case law according to which, the mere provision of an opportunity to access the work is sufficient for an “act of communication” to be assessed, irrespective of whether the users avail themselves of that opportunity in particular. Secondly, the Court held that the “act of communication” carried out by the manager of the news aggregation website was aimed at all the potential users of that website, who amounted to an indeterminate and fairly large number of recipients, constituting a “public” that falls within the scope of Article 3(1) of the InfoSoc Directive. As a result, the Court held that the provision of links to freely accessible works amounted to an act of “communication to a public”.

However, the CJEU concluded that the provision of links to works freely available online does not amount to an act of “communication to the pubic” within the scope of Article 3(1) of the InfoSoc Directive, owing to the fact that the same technical means were used (i.e. the internet) for both the initial and the subsequent communication acts, and the linked works were not communicated to a “new public”, i.e. a public that “had not been taken into account by the copyright holder when she/he authorized the initial communication to the public”. On the contrary, hyperlinks to works freely available online do not expand the circle of recipients of the work, as far as all internet users are able to access these works, and as a result should be considered as “part of the public taken into account by the copyright holders when they authorized the initial communication”

Notwithstanding its abovementioned assessment, the CJEU pointed out that the provision of a link to protected works, falls within the scope of the right of communication to the public, if it facilitates access to these works by circumventing restrictions that were put in place by the website on which the protected work was initially published. Under these circumstances, the hyperlink amounts to an intervention without which the internet users would not have been able to access the work, and as a result, they constitute a “new public” which was not taken into account when the copyright holder gave her/his authorization for the publication of the work under certain restrictions.

3) Criticism

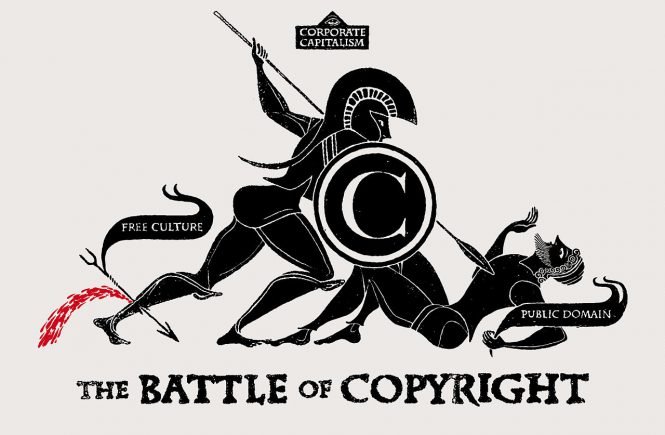

It is not contested that the Svensson case concerned a controversial and sensitive issue, which the CJEU would have to handle by striking a delicate balance of the conflicting interests. One the one hand, it is argued that if linking was to be thoroughly excluded from the protective scope of the right of communication to the public, then the objective of the InfoSoc Directive to achieve a high level of protection for the authors would be compromised. On the other, if every link to a protected work was to be considered as a communication to the public subject to the right holder’s prior authorization, this would have a detrimental impact on access to information and the functioning of the internet.

It is not contested either, at least not vigorously, that the denial of the Court to qualify the provision of hyperlinks as an act of communication, although decided without the delivery of an opinion of an Advocate General, achieved to reserve strong protection for the right holders whilst avoiding a rigid standing for the sake of internet’s functioning. What is contested though is the legal justification of the Court which as will be submitted, was correctly criticized as flawed and unprincipled, inevitably leading European Copyright to unneeded dead ends that the CJEU struggles to bypass in its recent GS Media and Soulier decisions.

a) Linking and the “forgotten” physical facilities doctrine

According to the agreed statement concerning Article 8 of the WCT, “the mere provision of physical facilities for enabling or making a communication does not in itself amount to a communication within the meaning of this Treaty or the Berne Convention.” This agreed statement was included in the WCT under the pressure of Internet service providers and telecommunication companies, which were investing in the development of their transatlantic infrastructures and were in need of guarantees concerning the limitation of their liability46, getting ready for their transition to the internet era. Despite the fact that this agreed statement was considered to be more of a restatement of the obvious assessment, that if somebody carries out an act that is not directly covered by the protective scope of the rights granted by the WCT, he/she cannot be held directly liable for the violation of the respective provisions of the convention, with secondary liability being the only possible tool for regulating his/her acts according to the relevant national laws, it could had served as a valid and sound legal basis for the declassification of linking as an act of communication to the public.

Interestingly enough, this agreed statement is implemented into EU law by recital of the InfoSoc Directive, which distinguishes the provision of the physical facilities for enabling or making a communication from the act of the communication itself. However, the CJEU has consistently ignored the “physical facilities doctrine” with respect to its linking string of rulings, losing a perfect chance to avoid what it latter proved to be its first and perhaps most crucial misconception: the characterization of the act of linking as an act of “making available”.

Strictly bound by the interpretative maxim of Recital 23 of the InfoSoc Directive,which brings about the broad interpretation of the right of communication to the public as a right covering all communications to the public not present at the place where the communication originates, the CJEU seems to have ignored that a hyperlink, in terms of the HTML language code is technically and grammatically signified by the so called “anchor tag” (<a>) and its indispensable parameter “href” which stands for “Hypertext Reference” and serves to specify the link‟s destination. This is the most basic command of the HyperText Markup Language (HTML), which is the standard authoring code language for creating web pages and web applications. In simple terms, a hyperlink is nothing more than a simple text that the web browser will interpret in a particular way and display as a clickable link.

In traditional copyright terms, the provision of access to a protected work through a hyperlink is a mere facility to access that work but is not itself a transmission of that work as the linker is not in control of the content of the work. On the contrary, the characterization of the act of the linker as an indispensable intervention without which the users could not be able to enjoy the works, from a technical point of view, would be an unsound and uninformed assessment. This conclusion is not altered even when taking into consideration that for the legal characterization of an act as an “act of making available”, the mere availability of the work will suffice, irrespective of whether the users avail themselves of the opportunity to access the available work, since the respective works were made available at a different time and in a different place that the linker under no circumstances can control or affect.

Last but not least, the exclusion of the application of the “physical facility doctrine” to linking, on the grounds that according to the provisions of the international treaties, a physical facility should be understood in terms of hosting infrastructure and hardware components rather than software code, should be counter argued by the simple consideration that the WCT was signed whilst the internet was still on its infancy. As a result, it would be a logical consideration to assess that the meaning of the concept of physical facilities should expand over time, in accordance with the respective technological development.

b) The shortcomings of the “new public” theory, the theory of “specific technical means” and the theory of application of “restrictive measures”

Below, the basic shortcomings of the “new public” theory, as well as of the criteria of the “specific technical means” and “restrictive measures” as mentioned above are submitted. Before entering into their detailed analysis, it is important to note the conflict of the above mentioned criteria, with the Vienna Convention on the law of treaties, as it has been explained analytically by the author of the “New WIPO Guide” and important contributor to the negotiations that led to the so-called “umbrella solution” approach, under the auspices of the WCT. According to Dr. Mihaly J. Ficsor , the criteria adapted by the CJEU in the Svensson case are unprincipled and in conflict with the context and the objectives of European Copyright law and their mother provisions (i.e. the WIPO Internet Treaties and the Berne Convention), and as such in conflict with Articles 3155 and 3256 of the Vienna Convention.

Thus, it is a settled case-law, that the interpretation of European Union law provisions is based not only on their wording, but also on the context in which they occur and on the objectives pursued by the rules of which they are part. Furthermore, there is an obligation of carrying out an interpretation which is consistent with international law where the provisions that have to be interpreted are intended specifically to give effect to an international agreement concluded by the European Union. And this is exactly the case with the interpretation of the rules of the InfoSoc Directive by the CJEU, since Recital 15 of the Directive states amongst its objectives, the fulfillment of EU’s obligations on the course of the implementation of the WIPO Internet Treaties.

i. The ungrounded extension of the principle of exhaustion to the right of communication to the public

It has been argued that the ruling of the CJEU on the Svensson case, according to which the provision of links to works freely available online (i.e. without technical restrictions) does not amount to an act of “communication to the pubic” on the grounds that the linked works were not communicated to a “new public”, encompassed an inappropriate extension of the principle of exhaustion to the right of communication. Indeed, to the amount that the copyright holder loses the ability to exploit his right of making his work available from the website that hosted the initial communication by means of linking, it can be argued that this specific dimension of his/her right of communication to the public has been exhausted . The only alternative viable interpretation for the justification of this complicated legal reasoning would be the assessment that within the authorization of the initial communication of a work to an unrestricted website, lays the implied consent of the copyright holder to the subsequent acts of making available to the public.

As far as Svensson case is concerned62, the CJEU ruling seems to reflect that the new public criterion could only be deemed as the unfounded exhaustion of the right of communication to the public. And such exhaustion is completely incompatible and directly conflicting with the international copyright treaties, which make explicit reference to the exclusive application of the principle of exhaustion only with regards to the right of distribution. In line with the above, Article 3(3) of the InfoSoc Directive implements the above mentioned provision by explicitly stating that the right of communication to the public, including the right of making available to the public are not exhausted by any act of communication to the public or making available to the public as set out in Article 3(1) and (2). As a consequence, a work needs to be authorized by the copyright holder each time it is made available to the public and not only when subsequent communications are headed towards a “new public” or carried out through “different technical means”.

ii. The monolithic perception of internet users as a single public

The CJEU considered that all internet users are potential recipients of online – freely available communications, and are therefore part of the same “public”. However, within the immenseness of the Internet, where every demand meets its respective offer and vice versa, it is at least unreasonable to consider that there is a single internet public that the right holder takes into account always as a whole. As far as Svensson case is concerned, the monolithic idea that a Swedish article is directed, for example, towards a French speaking public or that it is likely to be accessed by such a public, is far from reality and poses as one of the shortcomings of the CJEU’s “new public” theory. It is submitted here, that if it was not for the Court’s choice to perceive the public of the Internet as a single, monolithic public, then its “new public” theory might have been less problematic and more workable in practice.

iii. The “specific technical means” criterion and its conflict with the Berne Convention

As mentioned above, the “specific technical means” theory was developed when the CJEU, on the course of its ruling on the TVCatchup Case, assessed the legality of an online rebroadcasting service that provided its users with web access to television broadcasts, on the condition that they were already legally entitled to watch these broadcasts in the United Kingdom by virtue of their television license. Through the development of this theory, the Court has limited the application of the “new public” criterion, to cases where both the subsequent and the initial communication take place with the help of the same technical means.

As a result, the authorization of copyright holders for any subsequent communication is needed either when the subsequent communication takes place via different technical means or when, despite the use of the same technical means for both the initial and the subsequent communication, the latter is headed towards a new public. However, the adoption of this criterion is in conflict with the Berne convention, since its Article 11bis (1)(ii), which should serve as the interpretative guide for the Court, awards unequivocally to the rightholder, the exclusive right to control the cable retransmission and its rebroadcasting, irrespective of the technical means used for carrying out each single one of them.

iv. The dependence of the right of communication on the measures taken for restricting the access to the communicated work

As mentioned above, the application or not of “restrictive measures” to the accessed works, was used by the CJEU as a criterion for assessing whether linking constitutes an act of making available, and as such, an act of communication to the public within the meaning of Art. 3 (1) of the InfoSoc Directive. According to the reasoning of the Court, if the access to the website where the initial communication of the work was hosted, had been limited by the adoption of technological protection measures, such as pay-walls or subscription systems, then, authorization of the subsequent communications would be needed, irrespective of whether they would be carried out via specific technical means that were different from the ones used in the initial communication. However, this reasoning has been once again criticized as contrary to the respective international conventions. In particular, the aforementioned criterion would be in conflict with Article 5 (2) of the Berne Convention, since the adoption of the application of restrictive measures as a precondition for the enjoyment of the right of communication to the public, could be considered as a de facto formality.